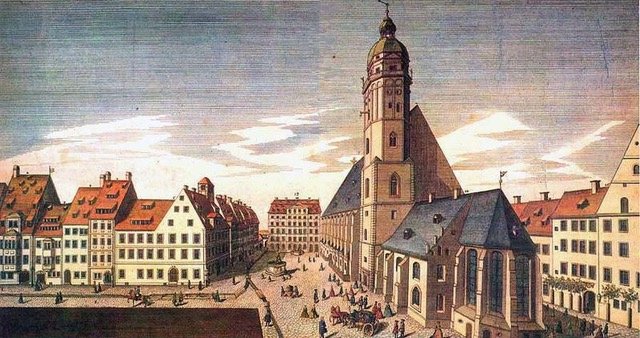

Thomaskirche, Leipzig, artist unknown, 1735

The Mass in B Minor is considered to be the summation of Johann Sebastian Bach’s art and one of the greatest masterpieces of Western sacred music. In approaching this work, one of the first things one notices is that Bach, a devout Lutheran church musician, put so much of his talent and energy into creating a massive and complex Latin mass that would never be performed in his lifetime and was not appropriate for either the Lutheran church services in Leipzig or for the Catholic court of the Elector in Dresden. And as an additional observation, the musical content is almost entirely comprised of adaptations of Bach’s existing works.

It is generally acknowledged that Bach intended to create a large work that would be his legacy: to show his talents and experience in choral writing and also to document the art of counterpoint, which, at the end of his life, was becoming old fashioned. What he created is a stunningly complex work, with twenty-six individual sections, all based on differing melodic material and written in a variety of styles. There are large Baroque fugal choruses, motet-like sections in the tradition of Palestrina, Gregorian chant, arias and duets in ornamented operatic styles and in the more modern “galant” style of the mid to late 18th century, full orchestral sections with unique instrumental obbligatos, and smaller continuo accompaniments—all masterfully interwoven to create an integral whole. Bach divided the work into four parts: Kyrie and Gloria; Credo; Sanctus; and the remaining sections of the mass, Osanna, Benedictus, Agnus Dei, and Dona nobis pacem.

While the Mass in B Minor as a whole was never intended for liturgical use, the oldest segments—the Sanctus, and the Kyrie and Gloria—were composed with performance in mind. Unlike other Protestant religions, the German Lutheran Church retained the mass, or Holy Communion, as its principal worship service. In Bach’s time in Leipzig, these three sections of the mass were still performed in Latin on feast days and holy days. The Sanctus was written for Christmas Vespers in 1724. It stands alone as a separate section in Bach’s B-Minor Mass, as it would have in the Lutheran service. In 1733, Bach composed a Missa Brevis, or short mass, to accompany his petition to Augustus III, the Elector of Saxony, to be appointed court composer. This short mass was composed in Latin and consisted of the first two sections of the Catholic mass, the Kyrie and Gloria. However, there was nothing “short” about this work. It is almost an hour in performance length and was written for full orchestral forces, such as those available at the Dresden court. Bach wrote four other short masses for performance in Leipzig or Dresden. It wasn’t until the late 1740s, near the end of his life, that Bach turned to creating the larger work that we know as the Mass in B Minor.

The mass begins with the traditional Kyrie, sung in Greek (“Kyrie eleison, Christe eleison” God have mercy, Christ have mercy). The three sections, organized on the division of the liturgical text, provide excellent examples of the varied musical styles in the mass. The opening Kyrie is a large Baroque fugal chorus for five voices and full orchestra. In the Christe, the duet that follows, Bach uses a simpler style, more typical of the “gallant” style, with less ornamented melodic lines and more straightforward instrumentation. The final section, the return to the Kyrie, is a slow and measured four-part chorus more in the style of the Italian Renaissance, although supported with a Baroque bass line.

The Kyrie is a section of supplication, asking for mercy. The Gloria is an extended hymn of praise and thanks to God for providing salvation, an important theme of the Reformation and probably the reason that the Kyrie and Gloria were retained as a part of the Lutheran service. The Gloria is divided into nine individual sections based on the text, and includes five impressive choruses, three solos and a duet. The solos and duet are all accompanied by various instrumental obbligatos. The Laudamus te, for soprano solo and strings, contrasts with the Christe duet from the Kyrie with a highly ornamented vocal line and complex accompaniment with violin obbligato.

First page of the Symbolum Nicenum (Credo) from Johann Sebastian Bach's Mass in B minor, BWV 232 (Source: Wikipedia)

The Credo, or creed, is a lengthy statement of Christian beliefs and an integral part of the mass. The composition of this large section dates from the late 1740s when Bach undertook the expansion of the original short mass. The Credo begins with a Renaissance-style fugue that uses the Gregorian chant melody for the fugal subject. The five vocal parts each present the subject over a Baroque “running bass” line that provides a more immediate sense of motion. The following chorus is a dramatic contrast, a lively reiteration and continuation of the text, in a style more similar to the 18th century, with full orchestra, trumpets, and timpani. In the Confiteor, a five- voice motet style chorus, Bach has slipped the Gregorian chant into the middle of the work sung by the middle voices (bass and alto) in canon and in the tenor part, in augmentation (sung with longer note values).

The two choruses of the Sanctus form the third large part in the B-Minor Mass. The first is a grand and majestic chorus, six-vocal parts in common time with a triplet figure that flows like large waves. The dramatic bass line, which repeats in loose passacaglia fashion, punctuates and relentlessly drives the movement forward. The Pleni sunt coeli is a lively Baroque fugue.

The final part is comprised of the remaining texts of the ordinary of the mass: the Osanna, Agnus Dei, Benedictus, and Dona nobis pacem. The Osanna is the only eight-part double chorus section in the mass. It is triumphant music that contrasts eight-part double chorus homophonic sections with four-part fugal sections, alternating between the two choirs. The mass ends with Dona nobis pacem.

Barbara Davidson

October, 2012